The AI Prisoner's Dilemma: Why Mega Cap Tech Spending May Enrich Everyone but Their Own Shareholders

The largest technology companies are locked in an AI arms race, spending hundreds of billions on infrastructure they cannot afford to forgo. History suggests that when every competitor is forced to make the same massive investment, the primary beneficiaries are consumers and smaller companies — not the investors footing the bill.

We begin with a premise that we believe is increasingly difficult to dispute: artificial intelligence will be a transformative technology. It will reshape industries, redefine productivity, and alter the competitive landscape across the global economy. The question for investors is not whether AI matters — it is whether the companies spending the most on it will be rewarded for doing so.

Our answer, informed by both economic theory and the long arc of technological history, is that the odds are stacked against them.

The Arms Race

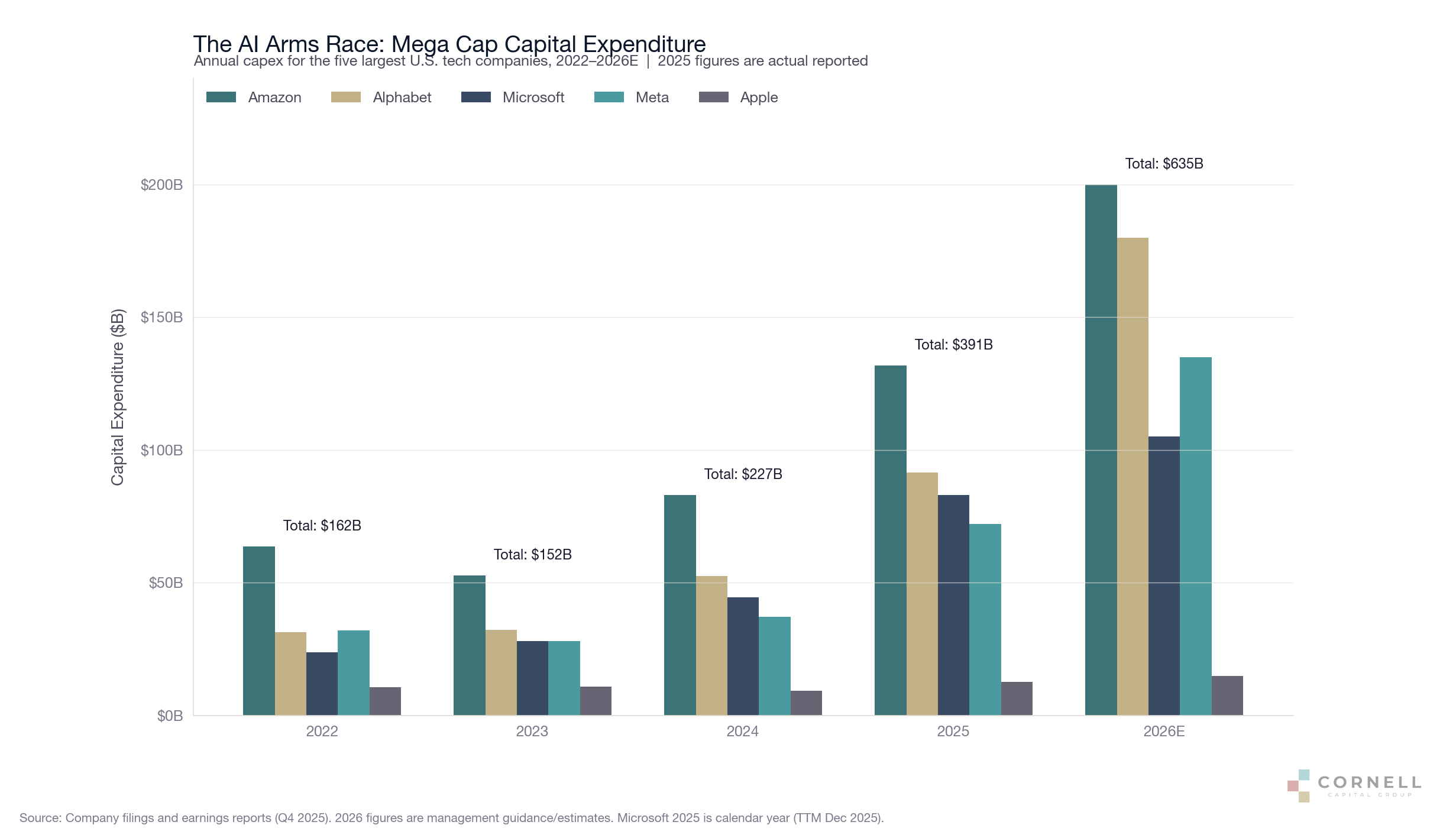

The numbers are staggering. In 2024, the five largest U.S. technology companies — Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Apple — collectively spent approximately $227 billion on capital expenditure. In 2025, that figure nearly doubled to $391 billion. Management guidance for 2026 suggests the total could exceed $635 billion. Goldman Sachs projects cumulative hyperscaler capex of $1.15 to $1.4 trillion between 2025 and 2027 alone — more than double the $477 billion spent from 2022 to 2024.

In 2025, Amazon spent $131.8 billion, predominantly on AWS infrastructure. Alphabet invested $91.4 billion — nearly double its 2024 figure — with 60% going to servers and 40% to data centers. Microsoft’s calendar-year capex reached $83.1 billion. Meta spent $72.2 billion. Looking ahead, the guidance for 2026 is even more aggressive: Amazon is targeting $200 billion, Alphabet has guided to $175–185 billion with CEO Sundar Pichai remarking that even this “still won’t be enough,” and Meta has guided to as much as $135 billion. Only Apple, with its asset-light manufacturing model, remains a relative outlier at roughly $15 billion.

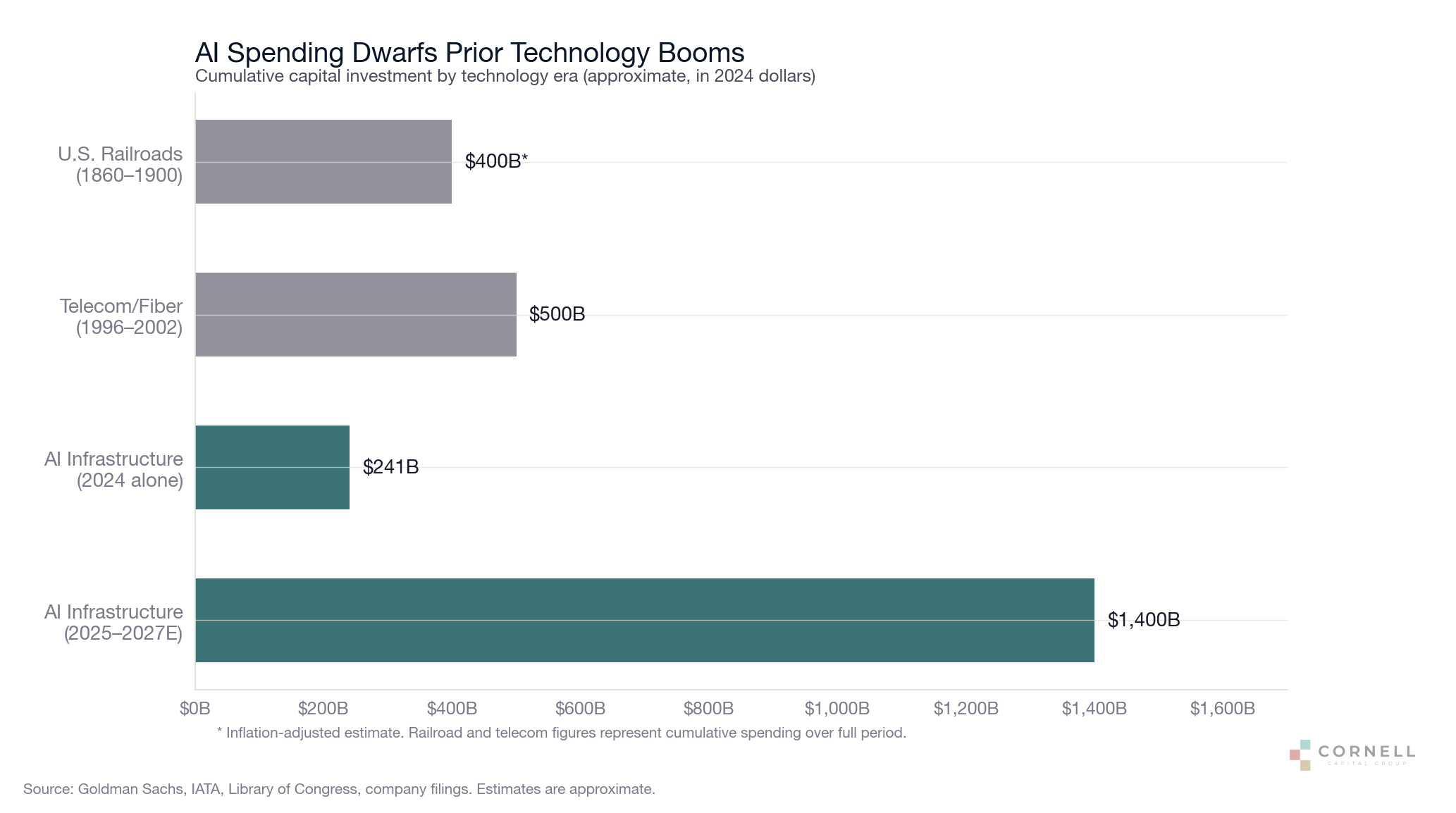

These figures represent a step-change in corporate capital allocation even after allowing for general inflation. To put this in context, the entire U.S. telecom industry invested approximately $500 billion in constant 2024 dollars — total — during the fiber optic boom of 1996 to 2002. The mega cap tech companies are now on pace to spend nearly triple that amount in a three-year window.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

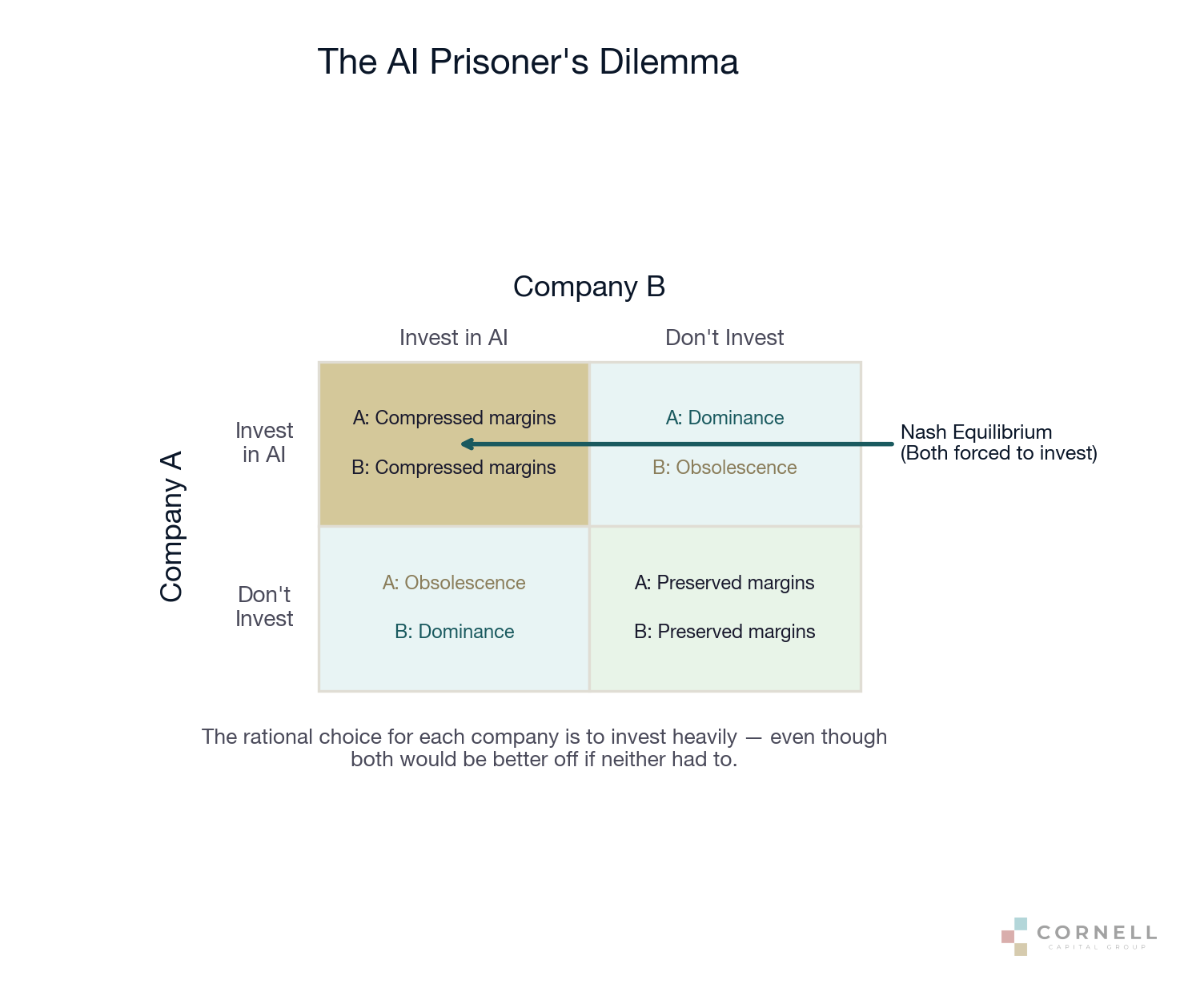

Why are these companies spending at such an extraordinary pace? The answer lies in a classic game theory framework: the prisoner’s dilemma.

Consider the strategic calculus facing any individual mega cap company. If a company invests heavily in AI and its competitors do not, it achieves dominance — capturing the market and earning outsized returns. If it fails to invest while competitors do, it risks obsolescence. The rational strategy, regardless of what competitors do, is to invest aggressively.

The problem is that every company faces the same incentive structure simultaneously. When all of them invest hundreds of billions of dollars, the result is not dominance for any single player but a mutual compression of margins. The massive capital outlays become table stakes rather than a source of competitive advantage. Each company is individually rational in its decision to spend, yet the collective outcome — an industry-wide capex arms race — leaves all of them worse off than if none had been compelled to invest at this scale.

This is the Nash equilibrium of the AI era: every major technology company is locked into a spending trajectory it cannot unilaterally abandon.

History Rhymes

This dynamic is not new. Technological revolutions have repeatedly demonstrated a consistent pattern: transformative innovations create enormous social wealth while destroying investor capital. The benefits flow overwhelmingly to consumers, workers, and downstream adopters — not to the companies making the largest investments.

The Jet Airplane and the Airlines

Perhaps no industry better illustrates this phenomenon than commercial aviation. The development of the jet engine in the 1950s was a world-changing innovation. It shrank the globe, enabled mass tourism, and transformed international commerce. For passengers, the benefits have been extraordinary — a flight from New York to Los Angeles costs approximately 80% less in real terms today than it did in 1960.

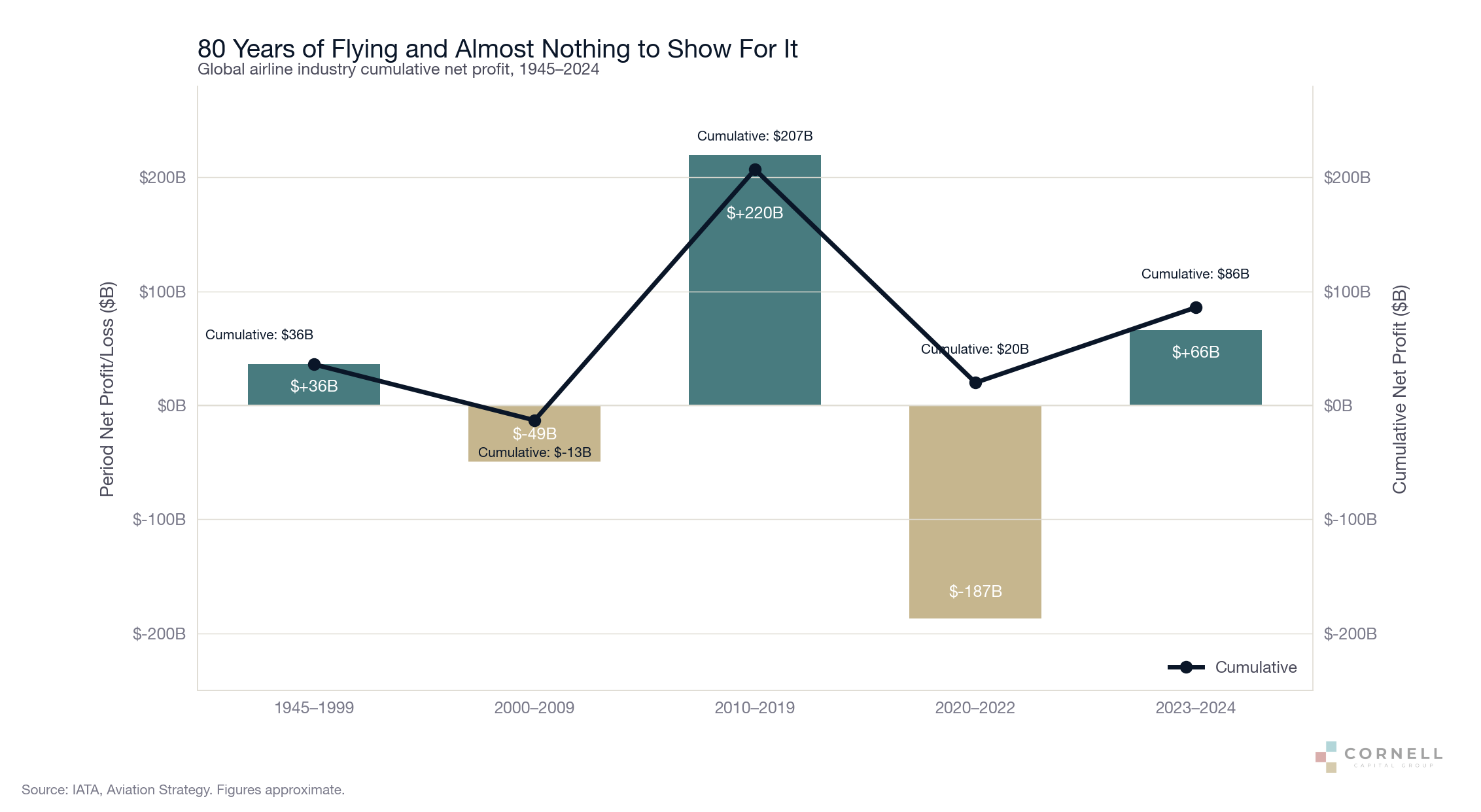

For investors, the results have been catastrophic. Over roughly 80 years of commercial aviation, the global airline industry has generated cumulative net profits of approximately $86 billion — a rounding error on the trillions of dollars in cumulative revenue. COVID alone wiped out nearly $190 billion in three years, more than erasing the industry’s most profitable decade.

The structural problem was persistent overcapacity and ruinous competition. Airlines were forced to buy the latest aircraft — first jets, then wide-bodies, then fuel-efficient models — not because the investments promised attractive returns, but because failing to invest meant falling behind competitors who did. The capital expenditure was a cost of survival, not a source of profit.

Warren Buffett captured the dynamic perfectly: “Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.” After purchasing substantial positions in four major U.S. airlines, Buffett ultimately sold the entire portfolio in 2020 at an estimated $5 billion loss — a painful illustration that even the world’s most celebrated investor could not solve the structural economics of the industry.

The Telecom Boom and Bust

The late 1990s telecom buildout offers another cautionary parallel. Following the Telecommunications Act of 1996, companies invested more than $500 billion into fiber optic cable, switches, and wireless networks — most of it financed with debt. The vision was compelling: an explosion in internet traffic would require vast amounts of new bandwidth. The vision was correct. The investments were not.

By 2002, more than 23 major telecom companies had filed for bankruptcy, including WorldCom ($30 billion in debt) and Global Crossing ($12.4 billion). Approximately $2 trillion in telecom market capitalization was destroyed, and 500,000 jobs were eliminated. Less than 5% of the fiber installed during the boom was ever “lit.”

And yet — and this is the crucial point — that overbuilt infrastructure enabled the next generation of technology companies. Netflix, YouTube, and the entire cloud computing industry were built on top of dirt-cheap bandwidth that existed only because telecom investors had massively overbuilt capacity and then gone bankrupt. The social wealth created by the fiber optic boom was immense. The investor wealth destroyed was equally immense. The beneficiaries were not the companies that laid the cable but the consumers and startups that used it.

The Railroads

The pattern extends further back. In the 19th century, U.S. railroad companies attracted more capital than any other industry in history to that point. By 1897, railroad stocks and bonds totaled $10.6 billion — roughly $400 billion in today’s dollars — compared to a national debt of just $1.2 billion. The railroads were magnificent engines of social progress, enabling continental commerce, the settlement of the West, and the industrialization of America.

They were also magnificent engines of investor destruction. Nine out of ten railroad companies failed during the Long Depression following the Panic of 1873. A quarter of all U.S. rail mileage went into receivership during the Panic of 1893. Dozens of duplicate routes competed for the same freight, creating chronic overcapacity that bankrupted wave after wave of investors even as the underlying infrastructure proved transformational for the economy.

Who Actually Benefits

The historical pattern suggests that the primary beneficiaries of massive technology investment are not the investors making the investments. They are the consumers who gain access to better and cheaper services, and the downstream companies that build on top of the new infrastructure.

In the railroad era, it was the manufacturers, agricultural producers, and merchants who benefited from cheap transportation — not the railroad shareholders. In aviation, it was the traveling public and the tourism, hospitality, and global trade industries that reaped the rewards of affordable air travel. In telecom, it was Netflix, Google, and a generation of internet startups that built billion-dollar businesses on the back of overbuilt fiber networks.

The AI era appears likely to follow the same script. As the mega cap companies pour hundreds of billions of dollars into AI infrastructure — competing fiercely with one another to build the largest data centers, train the most powerful models, and deploy the most capable AI services — the cost and quality of AI capabilities available to everyone else will improve dramatically. Smaller companies across every industry will be the beneficiaries of world-class AI tools available at commodity prices, precisely because the hyperscalers are competing so aggressively to win their business.

This is the paradox of transformative technology: the more companies spend, and the more fiercely they compete, the faster the technology becomes commoditized. And commoditization is wonderful for consumers but corrosive for the margins of the companies doing the spending.

Implications for Investors

None of this means that the mega cap technology companies are bad businesses. Many of them generate enormous free cash flow from existing operations, possess powerful network effects, and occupy commanding market positions. The question is whether the incremental returns on AI capital expenditure will exceed the cost of that capital — and whether the competitive dynamics of the AI arms race will allow any single company to sustain a durable advantage.

The historical evidence is sobering. In railroads, airlines, and telecom, the technology proved far more valuable to society than to the investors who funded it. The companies that spent the most on infrastructure often earned the least. The winners were those who built on top of the infrastructure rather than those who built the infrastructure itself.

Investors considering the mega cap technology companies at current valuations should ask a simple question: are they buying the railroad, or are they buying the businesses that the railroad will enable?

The answer matters enormously. History suggests that in a prisoner’s dilemma, the prisoners rarely escape.