In this video, we explore the history of the CAPE (Shiller PE) ratio, how it’s…

#52 Reflections on Investing : The Crash of the Bond Market

Would you believe, that long-term US Treasury securities, historically considered one of the safest investments, have now dropped more than the stock market did during the great recession of 2008? What are the implications for fixed income investments going forward?

Hello and welcome back to Reflections on Investing with the Cornell Capital Group.

It’s been a while since we’ve done one of these, but this is a bigger one today. We’ll be talking about inflation, interest rates, and the collapse of the bond market.

This is a subject that’s very near and dear to me because it’s what I wrote my PhD dissertation on. So, let’s start at the beginning, which is an important definition: What is meant by the nominal interest rate versus the real interest rate?

An easy way to think about it is that the nominal rate is the normal rate that you get when someone says a 5% bond. Meaning if you invest $100, you get $5 a year. That’s a nominal rate payable in dollars.

The real rate is your increase in purchasing power. So, if inflation were 5%, which it has been recently, then your real rate of return would be the nominal rate of inflation minus the nominal rate of interest of 5%, which is zero.

And the reason this distinction is very important to keep in mind is that investors are ultimately concerned about real rates. So, if inflation takes off and goes up from 2% to 5%, maybe to 7 or 8%, nominal rates have to go up along with it. And that means that bond prices must fall.

So, with that background, let’s do a little history. This subject of interest rates and inflation is one that we’ve addressed quite a few times in previous Reflections on Investing.

“Where do we stand at the Cornell Capital Group?

Well, quite frankly, we think interest rates are too low. We can’t understand why the 10-year treasury is as low as 1.2%.”Reflections on Investing #12 : The Ten Year Treasury Bond

At the time the rates were so low, two things were going on: The federal government was running very large deficits, and the Fed was buying the bonds issued by the Treasury and in doing so, producing added money. In other words, both fiscal policy and monetary policy were extremely expansionary in that circumstance. You’re likely to see inflation. You now know that nominal rates are going to go up, and if nominal rates go up, that means that bond prices are going to fall.

Well, you might say, “Well, the Fed’s going to come in and fight inflation.” But the way the Fed fights inflation is by raising nominal interest rates. So from the perspective of the pandemic, when Treasury 10-year Treasury rates were about 1%, the future looked very bleak. Either there would be inflation, or there would be a Federal Reserve policy to increase interest rates to fight inflation. In either way, long-term bonds looked to us as we said:

“Although we’re starting to entertain fixed income investments again, we still don’t see them as sufficiently attractive.

Now turning to risk, you’d say, “Well, there’s no risk of a 10-year fixed income investment if I put my money with the US Treasury.” Well, that’s only true if you hold it all 10 years. And here’s the problem: suppose you bought a 10-year Treasury when the yield on it was 1% and now it’s 2.2%. Well, because of the higher yield now, the price of the original bond falls. And in fact, you can calculate that it would have fallen about 14%. So, if you bought a one-year Treasury last year, you’re now about 13.3% underwater, 14% minus the 1%.

And because of the Cornell Capital Group, we fear that interest rates could rise a good deal more. That risk remains.”

(Reflections of Investing #28 : Fixed Income)

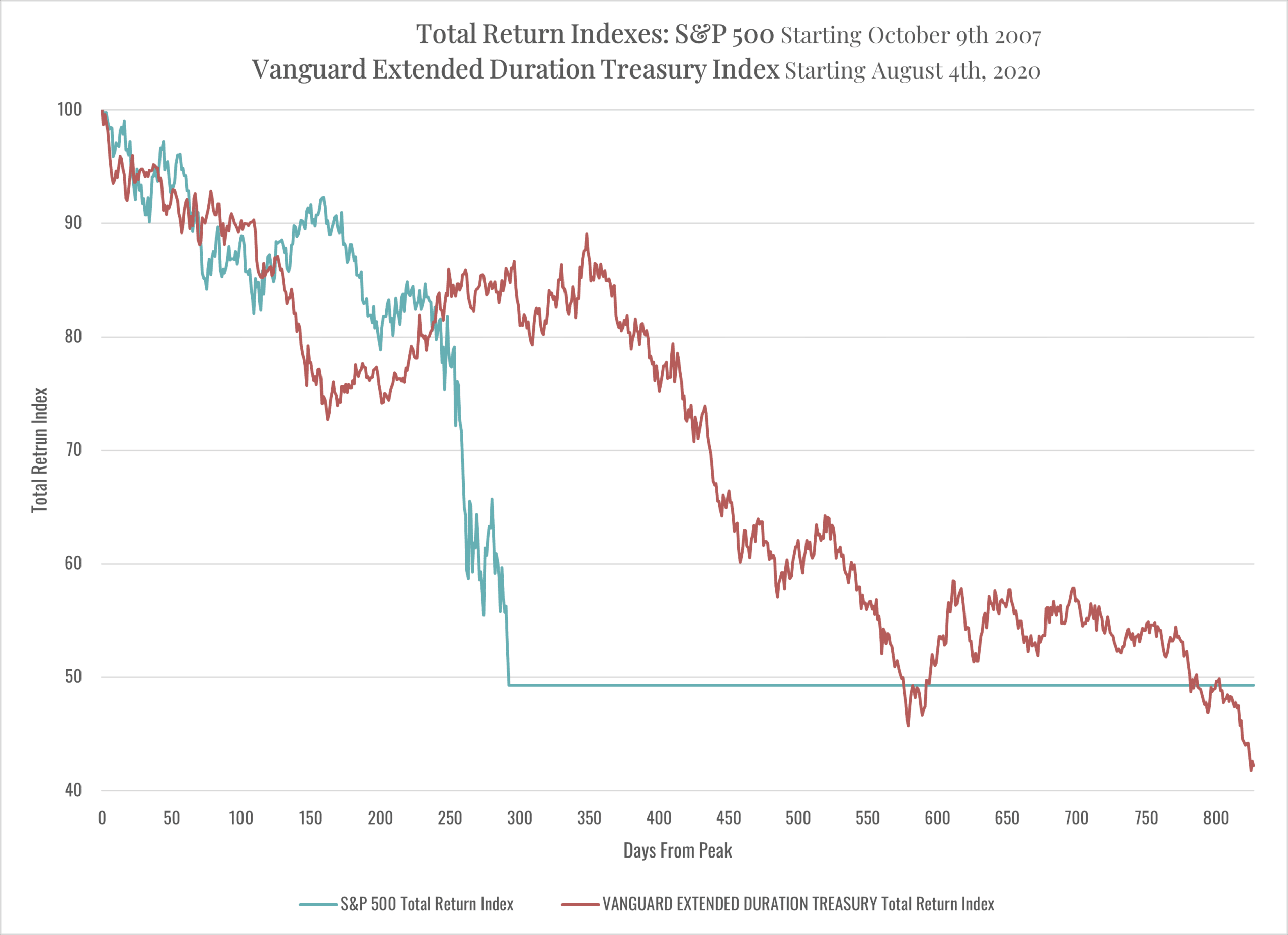

What actually happened over that two- to three-year period? And what happened was a bond market collapse of almost unprecedented depth.

Here’s an example: The chart showing here compares the drop in the S&P 500 during the financial crisis to the drop in the value of long-term Treasury bonds measured by an exchange-traded fund in the recent two- to three-year period. And the shocking fact is that Treasury bonds with promised cash flows dropped by more than the S&P 500 did during the financial crisis. I think that shows you how deep this collapse was.

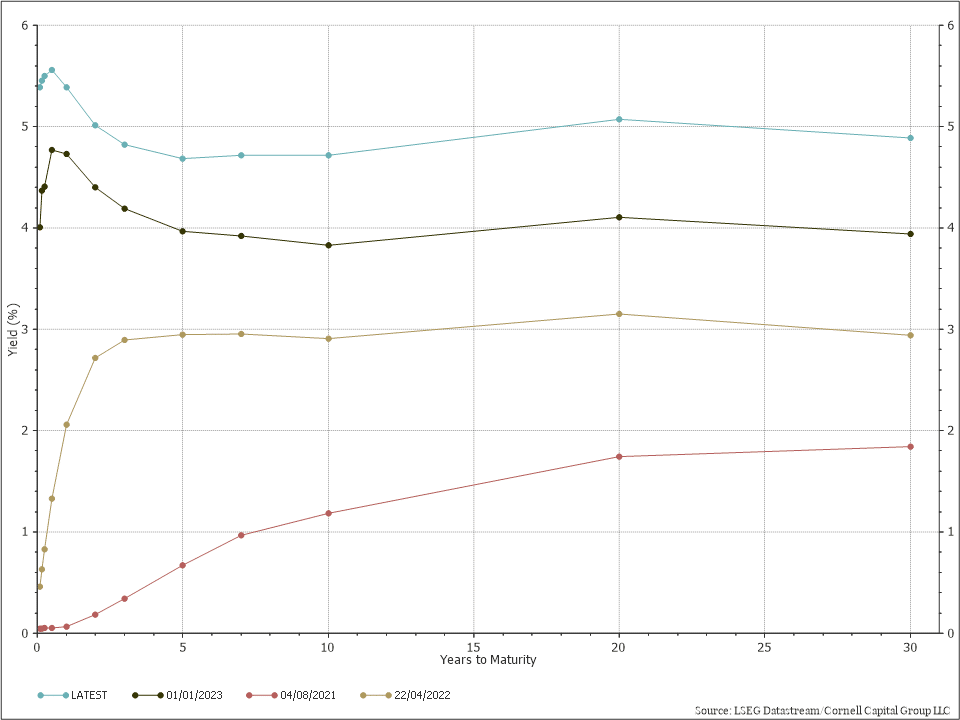

Now, here’s our next chart. It shows the yield curve. Remember what the yield curve is? It plots the nominal rate on a security compared to its maturity. And these are for Treasury Securities, and you can see now that current short-term rates are very high particularly compared to several years ago when they were virtually zero.

This is another aspect of this collapse in the bond market: the shift in the yield curve from sharply upward sloping to what is now called inverted.

To give you an extreme example of how deep this collapse has been, the Austrian government, during the period of most excessive monetary ease, issued a 100-year bond with about a 1% or less than 1% yield. The price of that bond, as you can see here, has dropped from 100, or 100 cents on the dollar, to less than three.

So, anyone who invested in a bond whose payment of interest was promised by the Austrian government, and they have never missed the payment, nonetheless, the price of that bond has dropped by more than 97%.

Given this collapse, and given that the Cornell Capital Group has been warning about this for at least two years, what do we think about fixed income now?

The first goes back to that yield curve chart. If we bring that back up, it shows that the short-term rates now, that is, interest rates on securities with less than a year maturity, are about 5.2%. That looks sufficiently attractive to us to be considered.

The problem, though, is they’re very short-term maturities. You get the 5 and a half percent, but six months from now, what if the Fed has succeeded in combating inflation and starting to cut rates? When you get your money back, you’re going to have to reinvest it, perhaps at a much lower rate.

Now, you could avoid that problem by buying a 10-year bond, but the problem with the 10-year bond is what if inflation takes off again and goes to possibly five or even 10%? Then you’re going to have a big loss on those bonds. So, trying to buy a long-term bond now to lock in current yields, we still think is a very risky strategy.

But there’s an alternative, and that is the so-called TIPS, which are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities. And here is the yield on TIPS. You can see that for most of the last decade, it was between half a percent and a percent. Then, during the period of maximum monetary and fiscal ease, the yield on TIPS actually fell to minus territory, minus 1%.

The real yield (this is not the nominal yield—these are inflation-protected, so this is the real yield) recently, as you can see on the chart, it’s climbed back to 2.4%, a decade high. So, by buying a TIPS, you can lock in a 2.4% real return and be fully compensated for all inflation. And that’s another thing that we’re looking at for our clients here at the Cornell Capital Group.

So, to summarize, we have lived through perhaps the worst period for fixed income in the last century. But that doesn’t mean that fixed income should be eschewed forever. In fact, just the reverse. We now think there are opportunities. If you’d like to discuss that with us, please get in touch with the Cornell Capital Group. Because in years going forward, fixed income looks attractive to us for the first time in the last five years.