The Continuing Market Melt-up The third quarter sustained the upward momentum in the market, which…

Investor Memo Q4 2025: Fiscal Deficits, Corporate Profits, AI and the Future of Equity Returns

Key Points

- S&P 500 returns (954.5%) following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis far exceeded expectations; driven by rising corporate profits more than economic growth.

- Future returns likely lower; volatility higher; disciplined investing is crucial.

- U.S. stock valuations (CAPE ~40) are historically high; risk of market decline.

- U.S. equities are expensive globally; better value found in other markets.

- AI’s impact is uncertain; competition and regulatory risks may limit shareholder gains.

Market Overview

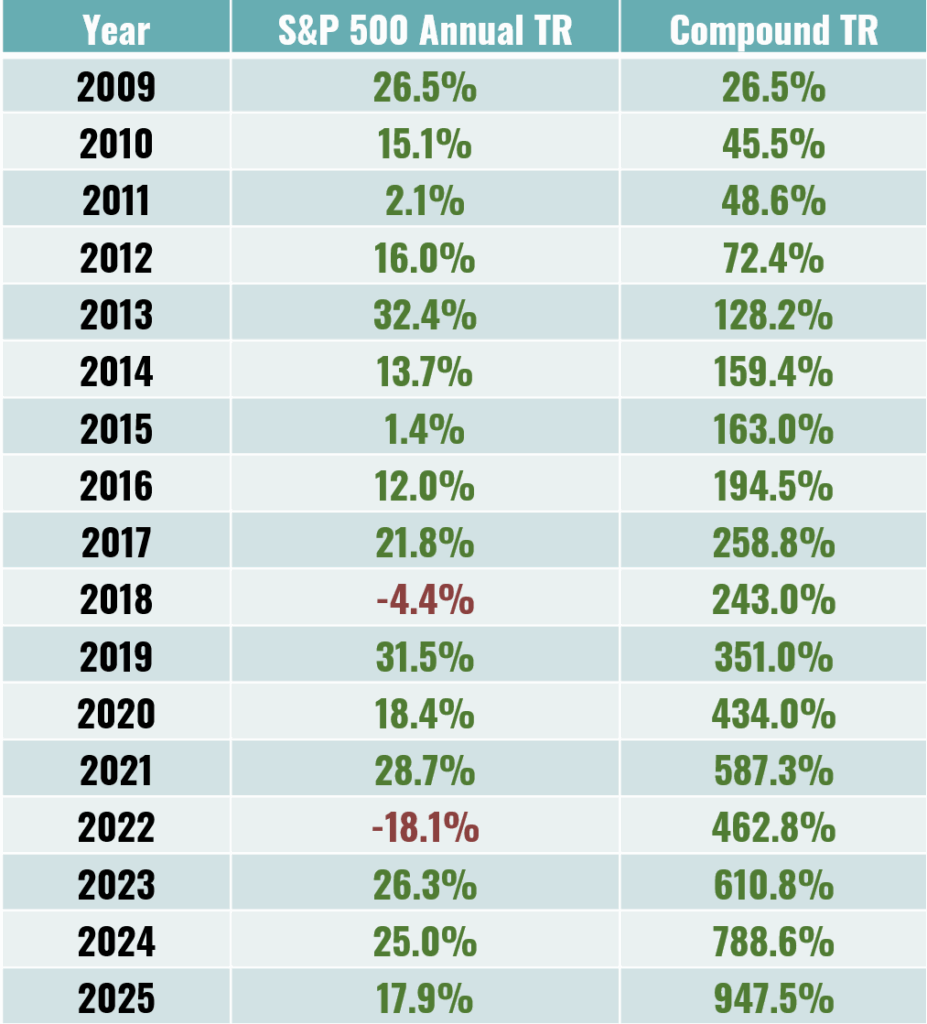

The past seventeen years have delivered extraordinary returns for U.S. equity investors. The S&P 500 rose 954.5% from 2009 to 2025 — a performance far exceeding what most rational valuation frameworks would have predicted at the start of the period.

Unfortunately for investors, the same forces that powered that exceptional run are now largely exhausted. Current valuations and global comparisons suggest that the next decade is unlikely to resemble the last. Expected returns should be meaningfully lower, volatility higher, and disciplined portfolio construction more important than ever. Let’s explore why.

Why the Last 17 Years Were So Exceptional

In any rational valuation framework, stock prices reflect the present value of expected future earnings. Sustained periods of exceptional performance can arise from only three sources:

- Economic growth

- A rising corporate share of the economic pie

- Falling discount rates

Economic growth, however, does not explain the experience of the past two decades. U.S. real GDP expanded only 48.5% over this period — roughly 2% per year, below its long-term historical average.

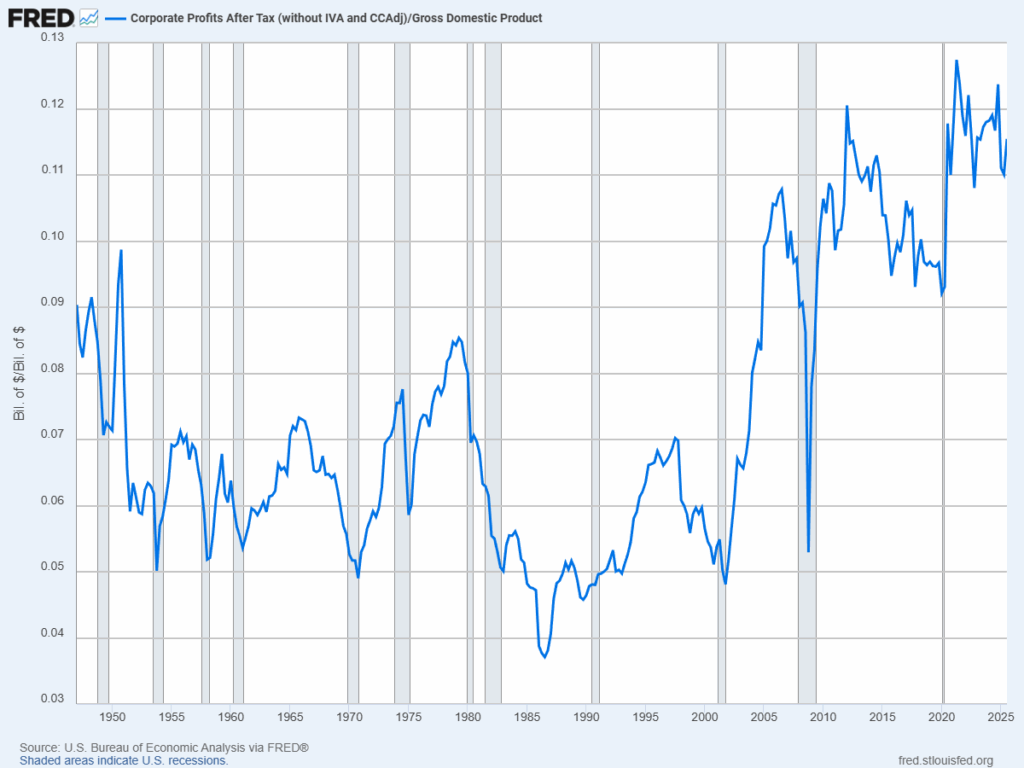

What did change dramatically was the share of national income captured by corporate profits. Corporate profits rose 138% – nearly three times the growth of the overall economy. This windfall reflects the combined effects of globalization, falling corporate taxes, the growing dominance of “superstar” firms, the increasing importance of intangible assets, and the powerful influence of persistent federal deficits.

Discount rates declined modestly as well, providing an additional tailwind. But the dominant driver of the market’s extraordinary performance was the unprecedented expansion in corporate profitability relative to GDP.

Why Extraordinary Returns Are Behind Us

Looking forward, the same three drivers now point toward a far more constrained return environment.

Economic growth is likely to remain near 2% real over the long run. Even optimistic assumptions about artificial intelligence suggest only limited and gradual improvements to sustainable growth.

Corporate profits already sit near historic highs as a share of GDP, and political as well as economic pressures are mounting. Holding today’s elevated profit share will be difficult; expanding it further appears highly unlikely.

Discount rates face powerful structural constraints. Large federal deficits and an enormous Treasury refinancing wall in the coming years make a sustained decline in interest rates improbable. In addition, the equity risk premium is near an all-time low. Further meaningful declines are unlikely.

One theme we have discussed before — but which we believe still receives far too little attention — is the role of persistent government deficits in supporting corporate profits and equity prices.

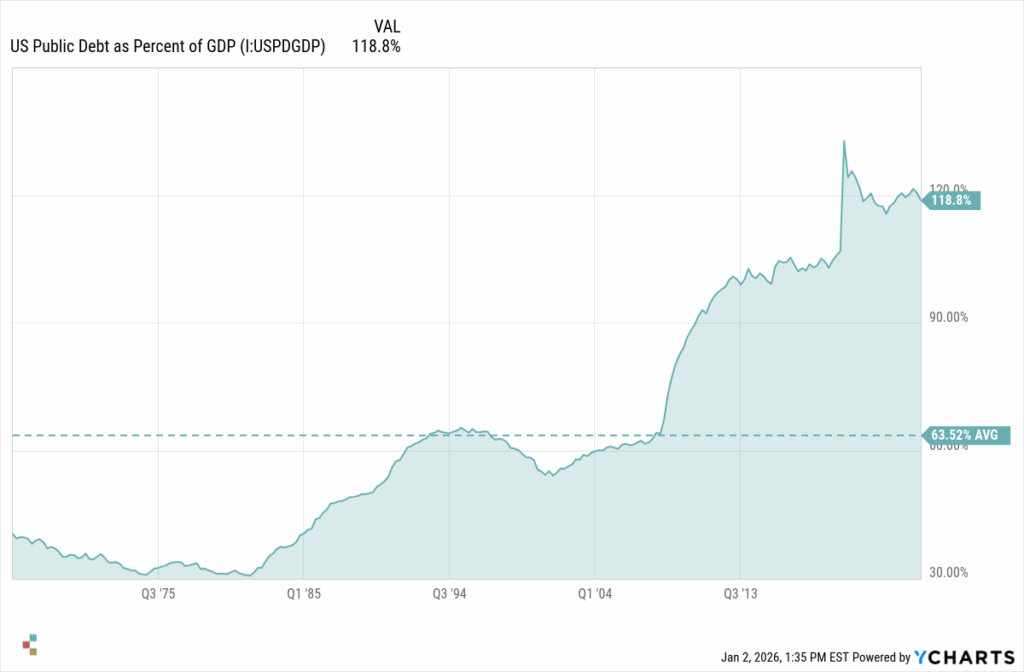

The chart below illustrates the first half of that story. It plots U.S. public debt as a percentage of GDP. Prior to the Global Financial Crisis, this ratio hovered around 60%. In response to the crisis, debt levels surged — and despite a long expansion and healthy GDP growth, they have continued to climb ever since. Today, U.S. public debt stands near 120% of GDP.

It is worth noting that the brief spike above 130% in 2020 was not part of the underlying trend. It reflected the pandemic’s abrupt collapse in economic activity rather than a structural shift in fiscal policy. What is unprecedented is nearly two decades of consistently large deficits during peacetime and healthy economic growth. The United States has never before run expansionary fiscal policy on this scale under such conditions.

If that is one side of the ledger, equity markets represent the other. Beginning in 2009, U.S. stocks entered a historic bull market. Over the next seventeen years, the market experienced only two declines — one of which was modest — with 2022 standing out as the sole truly difficult year. By contrast, there were eleven years in which returns exceeded 15%. On a compound basis one dollar invested in the market on January 1, 2009 with dividends reinvested would have increased by more than a factor of 10 by the end of 2025!

In our view, this is not coincidence. Persistent fiscal deficits have acted as a powerful and sustained tailwind for corporate earnings, valuations, and stock prices.

If this sounds too good to be true, we believe it probably is. Ever-rising government debt ultimately brings with it higher interest costs and growing refinancing risk. At some point, the combination becomes unsustainable. That inflection point may not arrive tomorrow — but it will arrive. And when it does, it is likely to mark a major shift in the investment landscape.

This is a risk we believe investors should be watching very carefully.

Current Valuations Leave Little Room for Error

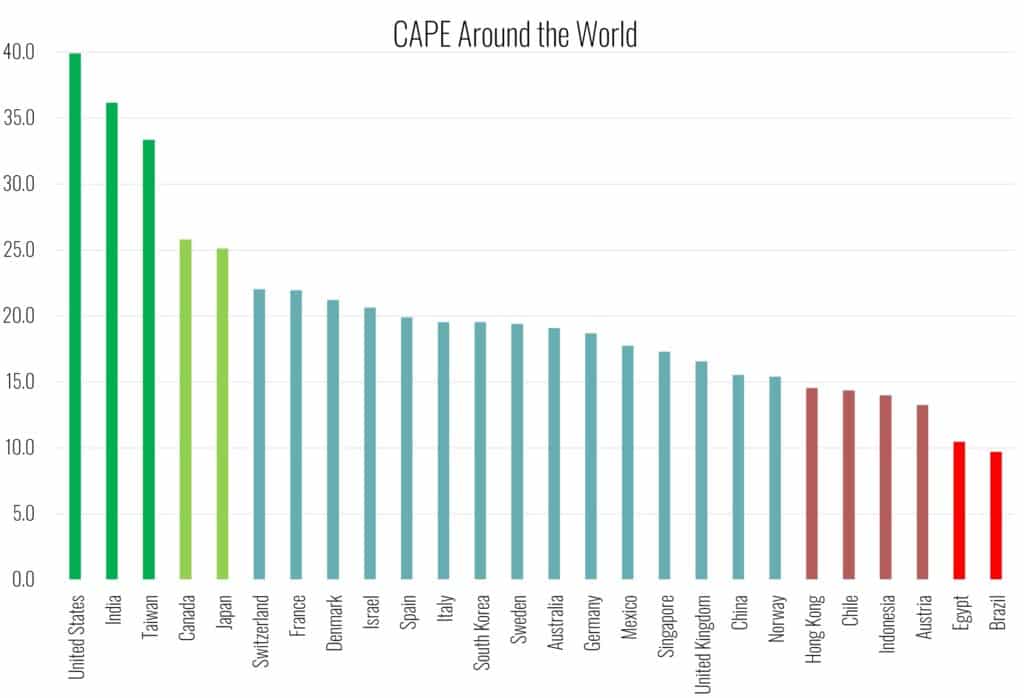

One of the most widely respected measures of long-term equity valuation is Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE). Today, the U.S. CAPE stands near 40—an extreme level by any historical standard. This compares with:

- A 1900–2025 long-term average of approximately 17

- A 1989–2025 average of roughly 27

- A long-term linear trend estimate near 26

From these starting conditions, there are only a limited number of plausible paths forward.

First, valuations could continue to expand. This would require sustained and unprecedented optimism, a willingness by investors to accept ever-lower prospective returns, and a belief that today’s economic and policy environment justifies a permanent break from historical valuation norms. This outcome, while possible, is unlikely in our view and does not represent a prudent base-case assumption.

Second, valuations could remain broadly stable at current elevated levels. In this scenario, future equity returns would be driven almost entirely by fundamental growth in corporate earnings and dividends, with little or no contribution from multiple expansion. While this outcome would avoid a sharp market correction, it would still represent a material shift from the experience of the past seventeen years. Returns would likely be meaningfully lower than investors have grown accustomed to, and volatility could remain elevated as markets periodically test the sustainability of such high valuation levels.

Third, and historically the most common outcome following periods of valuation excess, is some degree of mean reversion. A decline in the CAPE toward its recent average or long-term trend would imply a market drawdown on the order of 30%. A more complete reversion to the long-term historical average would imply a substantially larger decline, potentially approaching 60%. Importantly, such reversion need not occur abruptly; it could unfold gradually through a combination of market corrections, extended periods of muted returns, or earnings growth that fails to keep pace with optimistic expectations.

Taken together, these scenarios suggest that the asymmetric risk facing investors today is skewed to the downside. With valuations already elevated, there is limited scope for further upside driven by multiple expansion, while the range of plausible outcomes includes prolonged periods of modest returns or meaningful capital drawdowns. As a result, the exceptional returns generated during the long valuation expansion since the end of the global financial crisis should not be viewed as a reliable guide to future performance.

A Global Perspective: The U.S. Is Uniquely Expensive

Further insight can be gained by looking at the CAPE around the world. The chart below shows the current CAPE around the world. There are several key takeaways:

• The U.S. CAPE exceeds is 40

• Only India and Taiwan are close

• Most global market CAPEs cluster between 16 and 22

• Several major markets CAPEs near 10

The implication is unavoidable: U.S. equities are priced for perfection, while much of the world offers materially less expensive stock. Many investors remain heavily overweighted U.S. stocks largely because doing so worked well in the past — a form of circular reasoning that valuations strongly discourage.

What about the role of AI?

We would be remiss if we ended this memo without addressing artificial intelligence. In our view, AI has the potential to catalyze profound social and economic change. What remains unknowable — at least at this stage — is how and when that transformation will unfold. The uncertainty surrounding AI’s long-term trajectory is so great that we believe it is imprudent to use speculative projections of AI’s future as a primary foundation for current investment decisions.

There is, however, one aspect of AI that already carries critical investment implications, and it has little to do with the technology itself: the structure of competition and regulation surrounding it. Even when a technology delivers extraordinary social value, that value is not automatically captured by private companies or their shareholders. History provides sobering examples. Automobiles and commercial aviation revolutionized society, yet virtually every major automaker and airline went bankrupt at least once. As Warren Buffett famously observed, “If a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.”

Regulation and taxation could exert a similar influence on outcomes. If artificial intelligence delivers a major productivity boom, it is likely to do so primarily by replacing human labor. Should that occur, the political pressure to intervene will be intense. Governments will face strong demands to ensure that the gains from AI do not accrue disproportionately to a small number of corporations while large segments of the workforce bear the adjustment costs. The resulting regulatory and tax responses could significantly reshape how — and how much — of AI’s economic value ultimately reaches shareholders.

Against this backdrop, our decision as investors is one of deliberate restraint. While we closely monitor developments in artificial intelligence, we believe the combination of technological uncertainty, intense competition, and the high likelihood of regulatory and political intervention makes it difficult at this stage to identify durable business models capable of earning excess returns over time. Until clearer evidence emerges of sustainable barriers to entry and returns on invested capital meaningfully above the cost of capital, we believe patience is warranted. For now, we are content to remain on the sidelines rather than speculate prematurely on how this technological revolution will ultimately be monetized.

Looking Ahead

As we look beyond the immediate horizon, it bears emphasizing that successful investing is less about forecasting next year’s market moves and more about building portfolios capable of navigating a wide range of outcomes over the next decade. The exceptional returns of the past seventeen years were driven by a confluence of rare, largely non-repeatable forces. The environment ahead is likely to be more “normal”—marked by lower average returns, higher volatility, and wider dispersion across regions and asset classes.

In this setting, a focus on valuation, global diversification, and prudent risk management offers a more reliable path than chasing recent winners or speculative narratives. While technological innovation, particularly artificial intelligence, has the potential to reshape economies, the timing, scale, and beneficiaries of these changes remain uncertain.

The coming years will favor patience, adaptability, and a steady commitment to sound investment principles. While the future may not replicate the extraordinary gains of the recent past, investors who maintain perspective and discipline will be well positioned to protect capital, seize opportunities as they emerge, and make meaningful progress toward their long-term financial goals.

This memorandum is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as an offering of advisory services or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy any securities or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction.