The Continuing Market Melt-up The third quarter sustained the upward momentum in the market, which…

Investor Memo Q1 2024: The Market Throws Caution to the Wind

The S&P 500 ended the year 2023 at 4,769. During December, several leading financial firms were asked for their forecasts for the year-end 2024. The results are shown below. The most optimistic forecasts were by Fundstrat (a well-known bullish firm), Oppenheimer, and Yardeni. Considering the strong returns during 2023, four major firms, including Morgan Stanley and JP Morgan Chase, saw the market falling back.

In fact, the market threw caution to the wind. By the close of the first quarter the S&P 500 was at 5,254 blowing past all but the Yardeni year-end forecast and even surpassing the target of perennial optimist Fundstrat Global Advisers. That leaves us with two obvious questions. First, what drove the unexpected run-up? Second, what are the investment implications for the rest of the year?

Risk premiums continued to fall in the 1st quarter

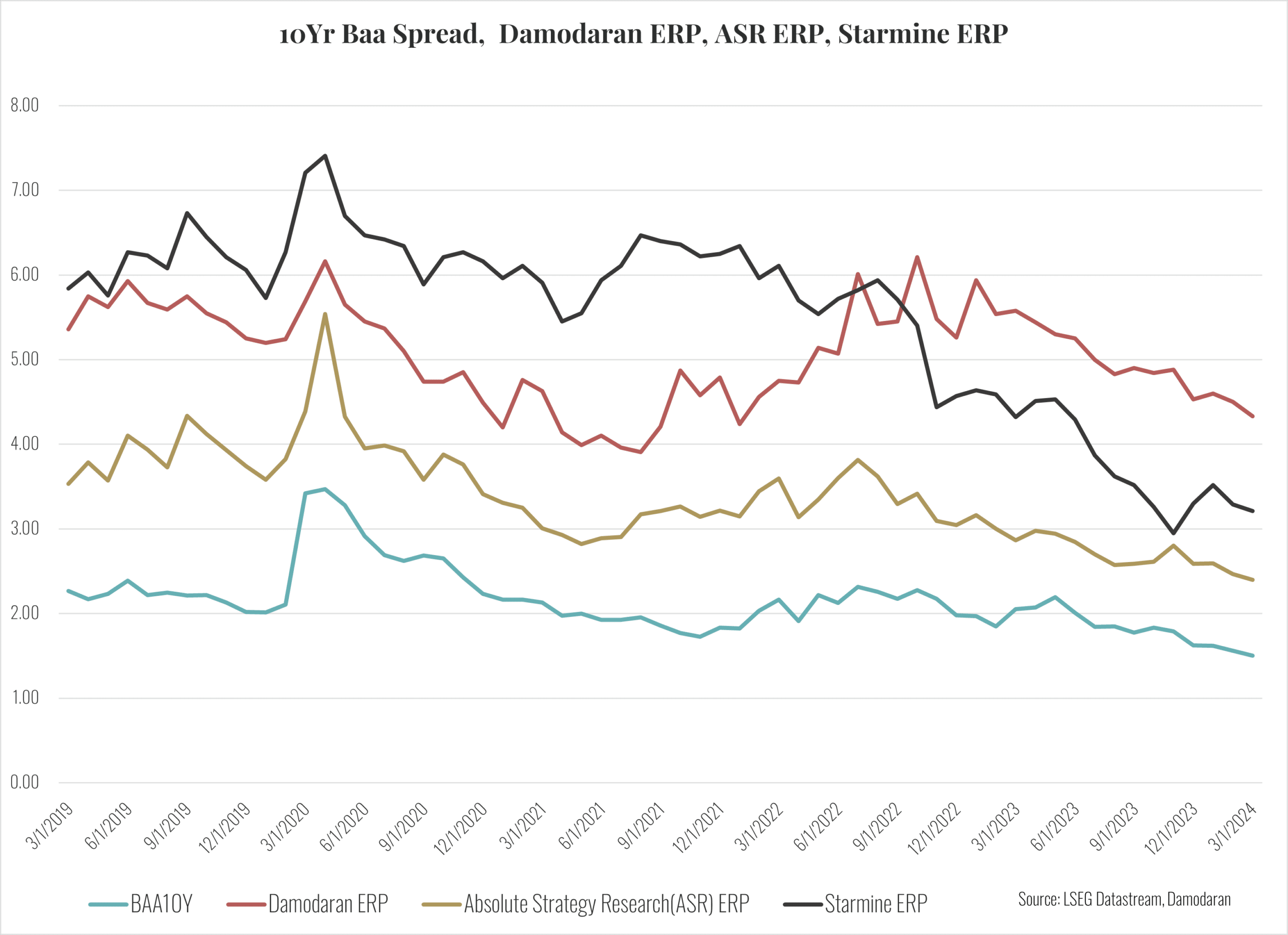

In our last two quarterly memos we stressed the importance of the equity risk premium for understanding the rise in stock prices. To estimate the equity premium, we used an approach advocated by Prof. Aswath Damodaran. While we think this is an excellent estimator, it is hardly the only one. Other estimates include those developed by Absolute Strategy Research and Starmine. In addition, there is no need to limit the analysis of risk premiums to the equity market. Credit spreads on fixed income securities of varying credit quality also provide information on risk premiums.

As an example, the next chart plots Damodaran’s implied ERP, the Absolute Research ERP, the Starmine ERP from the London Stock Exchange Group, and the credit spread between Baa rated bonds and ten-year Treasuries. They all tell basically the same story. Overall, risk premiums have been declining during the last five years and currently are near five-year lows. Because risk premiums are a key determinant of the discount rate and lower discounts rates lead to higher stock prices, declining risk premiums play a central role in explaining the high level of stock prices. However, two key questions remain regarding the risk premiums. First, are the current low levels a “new normal” or are the premiums likely to return to higher past average levels? Second, is it possible that premiums could fall further from here? For risk premiums to support rising stock prices, they must fall further. In our view this seems unlikely. But there is twist that depends on the role of the Fed.

The Stock Market and the Fed

In previous memos we proposed that one reason for the decline in risk premiums may be increased government management of the economy, particularly by the Fed. The current market obsession with Fed policy suggests we may have underestimated this effect. For instance, in response to the pandemic and the initial collapse of the stock market, the Fed responded not only by cutting rates to near zero, but by expanding programs introduced during the financial crisis and introducing a whole new set of policy tools. Among other things, the Fed began purchasing unprecedented amounts of securities including mortgage backed as well as Treasuries. Then, it expanded its support facilities to cover municipal and corporate bonds. Next, it created a term asset-backed securities loan facility to support the issuance of securities backed by student loans, auto loans and credit card loans. It also initiated an unprecedented main street lending program to support lending to small and medium sized businesses. Taken as a whole, the Fed ventured into territory that as recently as 2000 would have been considered beyond the scope of its powers. These interventions, coupled with more expansive fiscal policy, had a profound impact on the stock market. The S&P 500 which had dropped 35% in response to the pandemic largely recovered in the next three months and then raced upward to new highs.

The Fed’s recent action raises the question that if the central bank responds this aggressively to future financial disruptions, are we ever going to see long-run market declines of the type experienced in 1929, 1973, 2001 and 2008? It is these major long-term declines that historically have presented the biggest risk to stock market investing. If they are a thing of the past, if Fed responds rapidly and aggressively to stock market disruption, then the risk of stock investing has indeed significantly declined and risk premiums should be permanently lower leading to permanently higher market multiples and, thereby, higher stock prices.

To be fair we should note that the pandemic to which the Fed responded so aggressively was not only a stock market problem, but a full-on macroeconomic crisis. In initial response to the pandemic real GDP declined at a mind-numbing annual rate of 31.2 percent and unemployment soared to 15 percent. Given such a precipitous drop in economic activity, highly expansionary fiscal and monetary policy were clearly required. It is unknown how the Fed would respond to a large stock market drop that was not associated with an overall economic calamity. For instance, when the dot.com bubble burst in 2001 the Fed did not react in anything like the way it did 2020. The Fed may also be concerned that frequent interventions to support the stock market may conflict with its objective to control inflation.

Corporate Profits

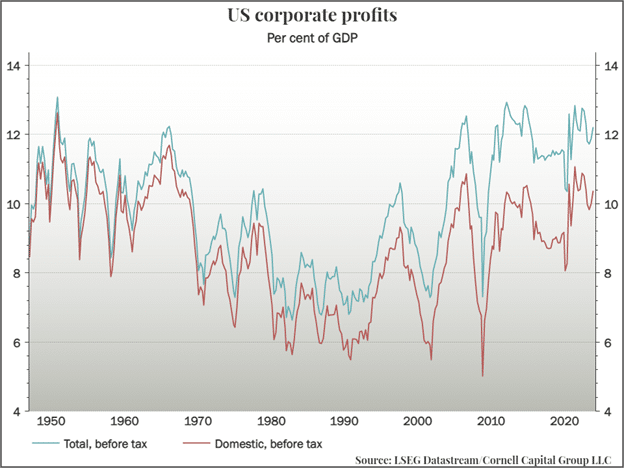

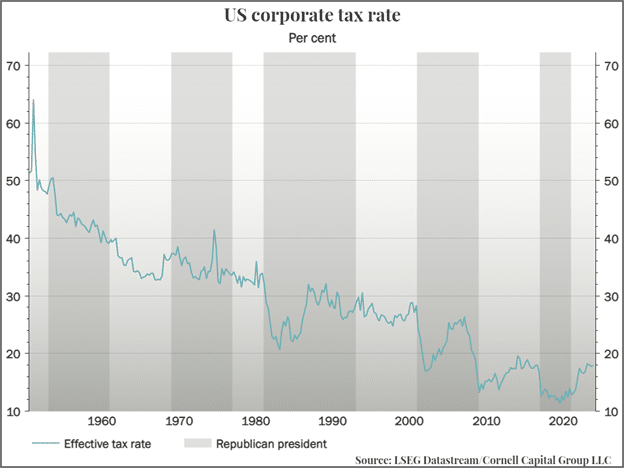

While our previous memos have predominantly focused on falling risk premiums to explain the uptick in stock prices, it’s essential to recognize that the risk premium influences only one aspect of the fundamental valuation equation—the discount rate. The other half is the forecast future cash flows that are discounted. Here we use corporate profits as a proxy for cash flows. Two elements come into play: before tax profits and tax rates. The two charts below show each of them.

With respect to before tax profits, the top chart shows that as a percent of GDP they have returned to levels not seen since the 1950s and 1960s and nearly double that of the 1980s. This is true whether we look at total profits or only domestic profits.

A big reason for the rise is corporate profits since 1980 are three big cuts in the corporate tax rates enacted during the administrations of Presidents Reagan, Bush, and Trump. The final cut by the Trump administration reduced rates a seventy-year low. Recently, however, political winds have begun to change, During the Biden administration effective corporate tax rates have risen and there is an active debate in Washington regarding further increases. Whether or not that occurs it is hard to imagine corporate rates being cut again, even if Trump is elected once again.

Putting the pieces together, we believe that increases in corporate profits have run their course as an engine for stock price increases.

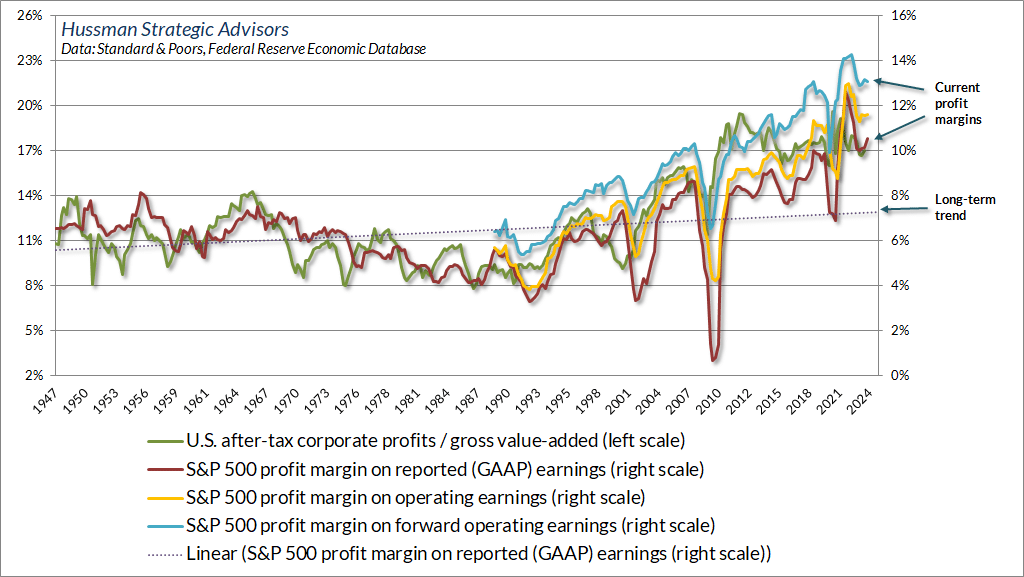

A similar picture emerges if we look at corporate profit margins as opposed to profits as a fraction of GDP. The chart below, taken from John Hussman’s latest memo, plots the corporate profit margins back to 1947 along with the long-term trend. No matter how they are measured, current corporate profit margins are near record levels and well above the long-term trend.

The question is where do we go from here? Corporate profit margins are constrained by both economic and political forces. It is hard to see them rising further. In our view rather than being an engine for pushing up stock prices in the years ahead, declining corporate profit margins could become a drag on the market.

Stock prices and the economic fundamentals: An analogy

You can think of the relation between the stock market and economic fundamentals (corporate profits and risk premiums) as analagous to a water skier (the market) attached to a boat (economic fundamentals) by a very flexible bungee cord. When the cord is contracting the skier can move a good deal faster than the boat and perhaps even race by it. However, eventually the skier must stall to allow the boat to pull ahead and begin to put tension on the cord. No matter what the short-run gyrations, however, in the long run the path of the skier is determined by the movement of the boat.

To apply the analogy to the current market, the economy (the boat) has been moving ahead but the skier (the market) has been moving a good deal faster. That suggests that the cord has become slack and to restore equilibrium stock prices will have to slow.

Conclusion

We ended our fourth quarter 2023 memo with the following words: We plan to be even more cautious and more fully hedged at the start of 2024 than we were at the beginning of the fourth quarter. Of course, this means that if the market continues to charge forward, we will underperform indexes such as the S&P 500, but we feel this is a reasonable price to pay for reducing the risks associated with either a market correction or a slow train to nowhere as the upward momentum comes to an end.

Well, the market did continue to charge forward and the cost to us was underperformance. Even though our returns were solidly positive, they did not match the performance of the S&P 500. Does that mean our cautious approach was unwise? We don’t think so. If you buy fire insurance and your house does not burn down the premium on the policy may seem like a waste – until there is a fire. At today’s level of stock prices, our analysis implies the need to be cautious, to focus on value stocks whose price exceeds our DCF valuations, and to continue to hedge. Although we strive for return, protecting the wealth of our clients remains a prime objective. And what we see as the frothy level of stock prices is a significant concern in that regard.

This memorandum is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as an offering of advisory services or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy any securities or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction.