Ai And Stock Market Valuation

In this article, we assume that AI, which we recognize has many different forms, will be a major economic success in that it will lead to greater productivity and rising GDP in the United States. The

Updated March, 6th 2024

In this article, we assume that AI, which we recognize has many different forms, will be a major economic success in that it will lead to greater productivity and rising GDP in the United States. The question for investors is how will it affect stock prices? That depends on whether you are talking about the stock prices of selected individual companies or the value of the aggregate market. We start first with the aggregate market and then turn to individual stocks.

Technological breakthroughs, of which we assume AI will be an example, increase social wealth by increasing the goods and services that can be produced from a given set of resources. This is measured by the growth rate in productivity. Productivity growth is the key determinant of real GDP growth per capita which, in turn, determines the standard of living. The primary source of productivity growth is technological innovation.

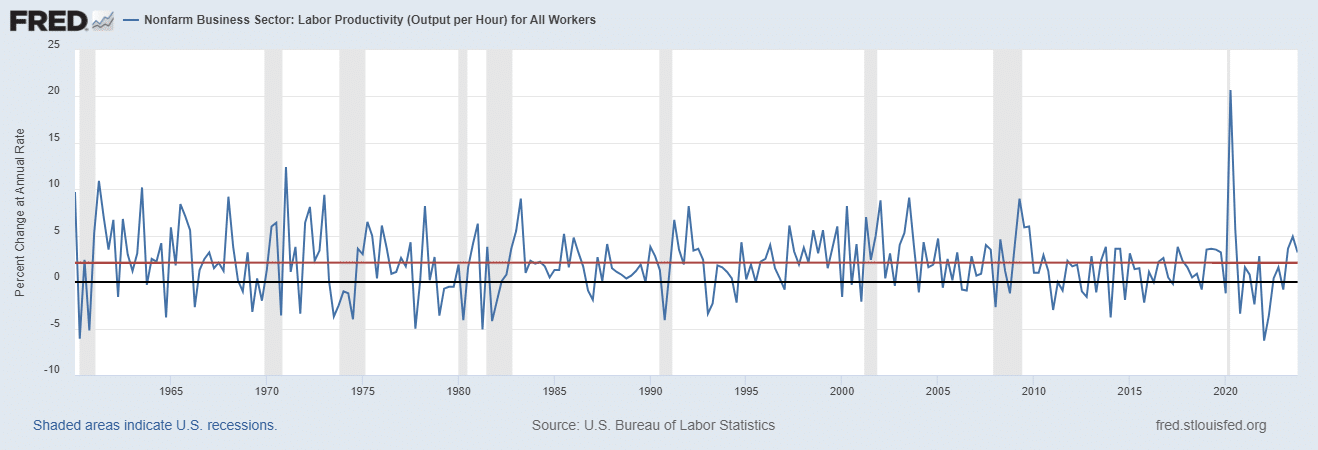

The chart below from the Federal Reserve plots quarterly productivity growth, stated as an annualized rate, in the United States from 1960 through 2023. The first thing to note is that the rate of increase is not large, averaging only 2.0% per year. The second thing to note is that the growth rate has been highly variable, tending to fall recessions and rise in recoveries with a good deal of added random variation. Despite the fluctuations, there has been little trend in the average growth rate since 1960. Furthermore, it is difficult to tie productivity growth to specific innovations such as the rise of computers and the development of the internet. Back in 1987, Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Solow famously noted that “ You can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics.”

Considering the chart, even if the impact of AI is great, possibly greater than that of the computer revolution or the internet, it is hard to see U.S. productivity growing significantly faster than 2% in the long run. However, the growth rate is likely to remain bumpy as it always has been. Whereas AI will make people more productive on average, many people will lose their jobs and others will have their lives upended. This will lead to costly political battles that are likely to make the acceptance of AI uneven.

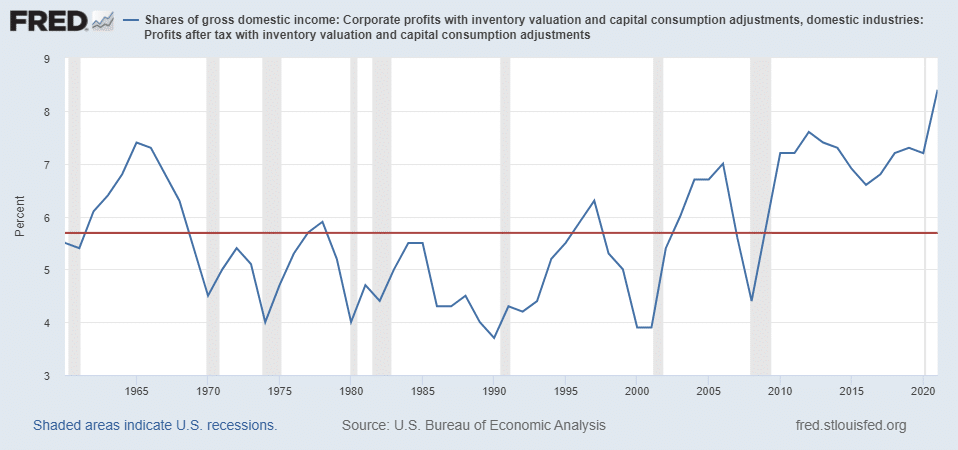

But stock prices do not depend on the social wealth a technology creates, they depend on corporate profits. As shown in the following chart, corporate profits have averaged slightly less than 6% of GDP from 1960 to 2023, although the fraction has been closer to 8% in recent years. This suggests that in the long run AI companies can expect to capture only about 8% of the wealth created by AI.

Putting the pieces together, the development of AI is unlikely to have a further pronounced impact on the level of stock prices generally, given that the market is forward looking and much of that impact has likely already been incorporated into prices. However, what is true in the aggregate need not be true for individual companies, such as Nvidia, which may potentially reap large profits from AI. However, in the case of individual companies, new problems arise.

First, as stressed by Cornell, Cornell, and Cornell (2021), a new technology does not translate into value creation for a company that adopts it unless it produces returns on invested capital (ROIC) in excess of the cost of capital. To earn excess returns, there must be barriers to entry that prevent competitors from adopting the technology, entering the business, and driving down the ROIC to the cost of capital. For instance, two of the great technological innovations of the 20th century were automobiles and airplanes. In tandem, they produced a vast amount of social wealth. Unfortunately, neither produced much wealth for investors because competition was brutal. Virtually every American car company and airline went bankrupt, some more than once. Regarding airlines, Warren Buffett quipped, “ if a far-sighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.” The vast bulk of the wealth that was created by automobiles and airplanes flowed to consumers, not investors. The fact that AI appears to be a general tool means that barriers to entry are likely to be limited. If so, it will be difficult for individual companies and their investors to reap much of the rewards in the long run.

Of course, there will be exceptions. While a majority of the startups that arose during the internet boom around 2000 failed, a few Amazons did emerge and produce great investor wealth. But there were precious few Amazons, whereas at the height of the boom virtually every company and their investors in the emerging internet space believed that it was going to be a big winner. This is an example of what Cornell and Damodaran (2020) call a big market delusion. The hallmark of a big market delusion is when all the stock prices of firms employing a new technology rise together even though many are in direct competition with each other and with established firms in the industry. Investors become so enthusiastic about the new technology that each firm is priced as if it will be a major success story. As a result, the aggregate value of stocks of companies employing the technology exhibit a fallacy of composition in which the sum of the parts (the sum of the market values of the individual firms) exceeds any reasonable estimate of the total value of the new business.

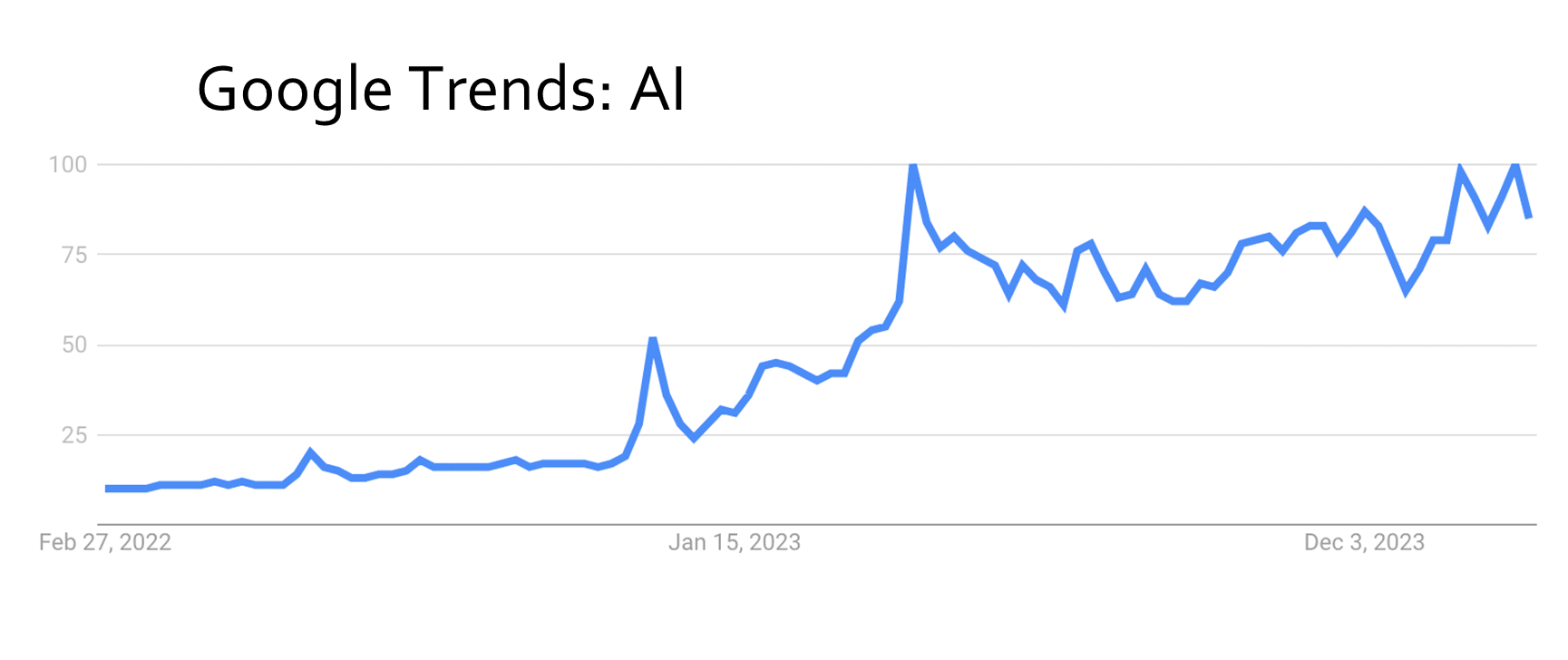

In our view, a big market delusion could be emerging in the case of AI. Virtually any company involved with AI in any way is talking up the opportunity. More generally, the financial media has been gushing about all the new doors that AI will open. A good indicator of the recent enthusiasm in AI is Google Trends, which measures relative the level of search interest for a particular topic. The chart below shows the surge in searches for the term “AI”. AI goes from being an also ran to being one of the most searched terms on the internet.

The second problem for individual companies is that along the value chain one company’s profit is another company’s cost. Nvidia has a unique position in the AI value chain because it currently designs chips for which there is a particularly high demand. Not surprisingly, analysts are predicting that Nvidia will sell a lot of chips at high margins. But that means that everyone who buys those chips for their hardware and related software applications pays a high price. That cuts into profits unless the high costs can be passed on. But if the high costs are passed on it is disadvantageous for final customers of AI products. Putting the whole value chain together, the social value created goes back to the increase in productivity.

Third, the foregoing assumed that at least some firms, Nvidia is a particular example, had barriers to entry that were sustainable in the long run. That is the only way they could continue to increase sales while retaining high margins. History suggests that that is a heroic assumption. It clearly proved to be false for airlines and automobiles. But does it hold for Nvidia? Already doubts are surfacing. Will INTC, AMD, TSMC, and others sit on their hands, allowing Nvidia to forever own the super-chips industry? Not likely. AMD already claims to have a chip that’s supposedly 25% faster than Nvidia’s best, at one-third the price. The force that drove Nvidia valuation past $2 trillion is likely to attract a lot of competition.

Finally, we have yet to mention what may be the most important issue for investors in individual companies – pricing. Sticking with the Nvidia example, following a bullish earnings announcement on Thursday May 25, 2023, the company’s market capitalization rose by more than $180 billion, the second largest dollar increase in history for any company. Nvidia then topped that with a record $275 billion increase in market capitalization following another earnings announcement on February 22, 2024. As a result of these run-ups, Nvidia’s market cap exceeded $2 trillion, surpassing both Amazon and Google to become the fourth most valuable company in the world. For investors buying at that valuation Nvidia’s future must be remarkable indeed if they are to make a reasonable return.

Putting the pieces together, at the Cornell Capital Group we fear that one of the doors that AI will open is an opportunity for investors to lose a lot of money. As was the case for electrical vehicle stocks in 2021, companies in the AI space are beginning to be priced as if they will all be big winners.[1] This is true even though some firms are customers of others. While AI is likely to be a major innovation, it is not likely to be a bonanza for investors buying in at current prices. Unfortunately, there is no way for Warren Buffett to protect those investors by shooting down AI.

[1] See Cornell, Cornell, and Cornell (2023) for analysis of the electrical vehicle market.

References

Cornell, Bradford, and Aswath Damodaran, 2020, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implication, Financial Analysts Journal, 76 (2), 15-25.

Cornell, Bradford, Shaun Cornell, and Andrew Cornell, 2021, Valuing the Automotive Industry, Cornell Capital Group, November 11, 1-14.

Cornell, Bradford, Shaun Cornell, and Andrew Cornell, 2021, Big Market Delusion: The Case of Electric Vehicles, Journal of Investing, forthcoming.